Cartoon Creates Their Own World With Their Drawings

Dig into the details that make comics unique, and try your hand at some activities.

Chris Gavaler

Sep 16, 2021

Illustration by Mohammed Fayaz for Drawn to MoMA

Style Has Meaning

Ask two people to draw the same thing and the styles of their drawings may vary radically. The same is true for drawings in comics. You can have the same plot with the same characters, but the look of those characters—the expressive lines that make up their bodies and the settings they inhabit—will feel different depending on an artist's style.

On one end of the spectrum, you might create a comic composed of simple cartoon figures, loose gestural drawings, or just stick figures or silhouettes. In each case, the amount of detail is minimal. They are reduced to their most essential parts. On the other end of that same spectrum, you find images with a lot of details, such as photorealistic drawings and actual photographs. Below is an image by Carolyn Capps from a graphic novel she and I are creating together. The amount of detail is unusual for works published in the comics medium.

Carolyn Capps. Into Night #36. November 2020

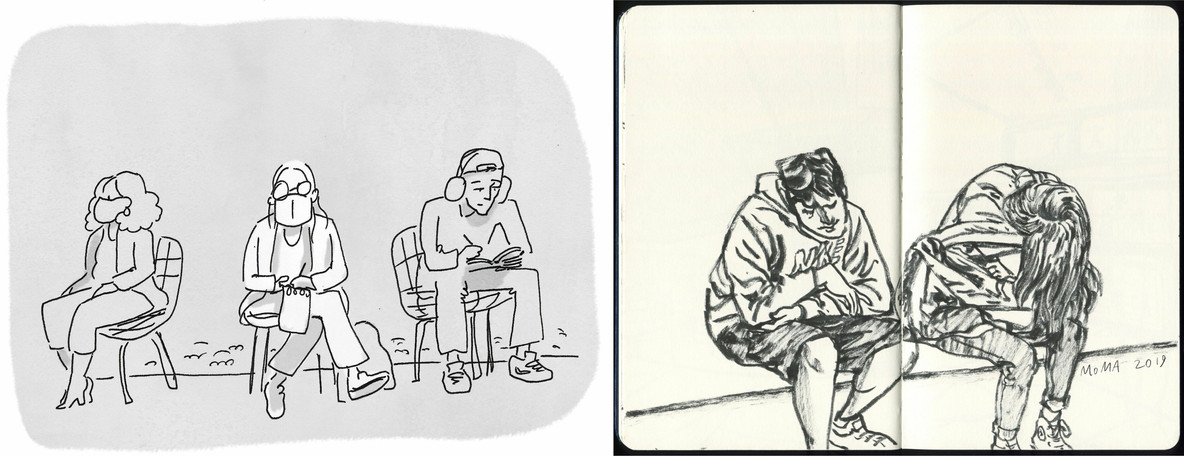

But most images fall somewhere in the middle of the spectrum. Compare the way Sofia Warren draws herself and two others watching a performance (below left) to Guno Park's depiction of two Museum visitors resting on a bench. The subject matter is similar, but Park's detailed style and Warren's sparse style create different effects that then can elicit different reactions in viewers.

From left: Illustration from Sofia Warren's "Feel This" for Drawn to MoMA; Illustration by Guno Park for Drawn to MoMA

Illustration by Anna Haifisch for Drawn to MoMA

Words Are Images Too

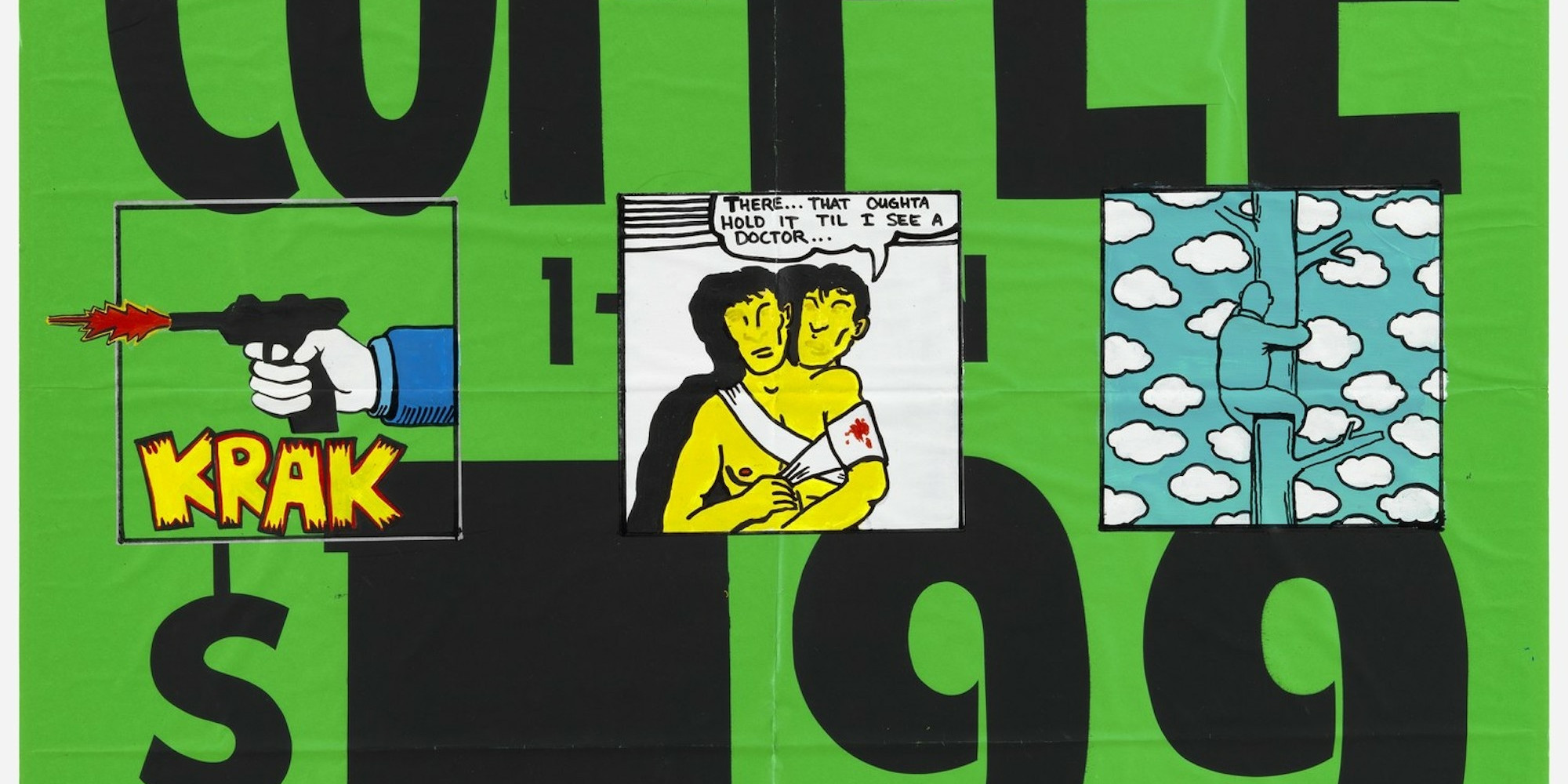

Words also have to be rendered in some kind of style. This can look like anything from your own personal handwriting to meticulously designed graphic art. In traditional comics, sound effects tend to be drawn by the primary artist in a highly expressive style ("Ka-BOOM!"). Speech and narration are drawn by a letterer in a comparatively unobtrusive style—except when a character's words suggest volume or emotion through a larger size or a darker rendering. Many comics artists use computers especially for text, but if you decide to use an electronic font, make sure it still relates visually to the images around it.

Illustration by Joanna Avillez for Drawn to MoMA

Illustration by Grace Robinson for Drawn to MoMA

You, too, will develop your own preferences. Should the lines that make the bubbles resemble the lines that make the characters? What if each character's word containers look like that character, so readers know who's speaking even if no figure appears?

Combining Words and Images

Unlike other kinds of images, words have meanings independent of how they're drawn. Think about how the meaning of a set of words relates to the image they are part of or next to. There are four basic relationships to consider: words and images can duplicate, complement, contrast, or diverge.

When they duplicate, the words and the image around them communicate roughly the same thing. This is the norm for children's picture books because the simplistic relationship helps with language acquisition. Illustrated versions of the nursery rhyme "Jack and Jill went up the hill to fetch a pail of water" typically include a young male figure and a young female figure carrying a bucket up a hill to a well. If you're not making a children's comic, though, that redundancy is something to avoid. Words and pictures should each bring something unique to their combinations.

When words and pictures complement, each adds something different to a unified effect. If a caption box frames the words, "Jo watched sitcoms all night," above a drawing of a figure sitting on a couch laughing, the combination is complimentary. You don't know that Jo is laughing unless you look at the image, and you don't know why Jo is laughing unless you read the words.

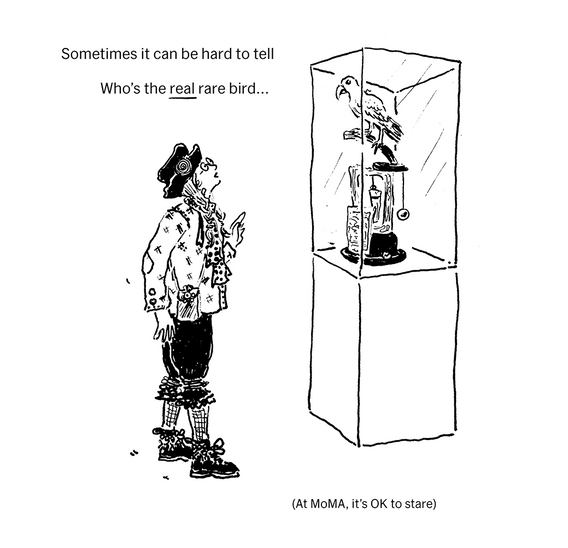

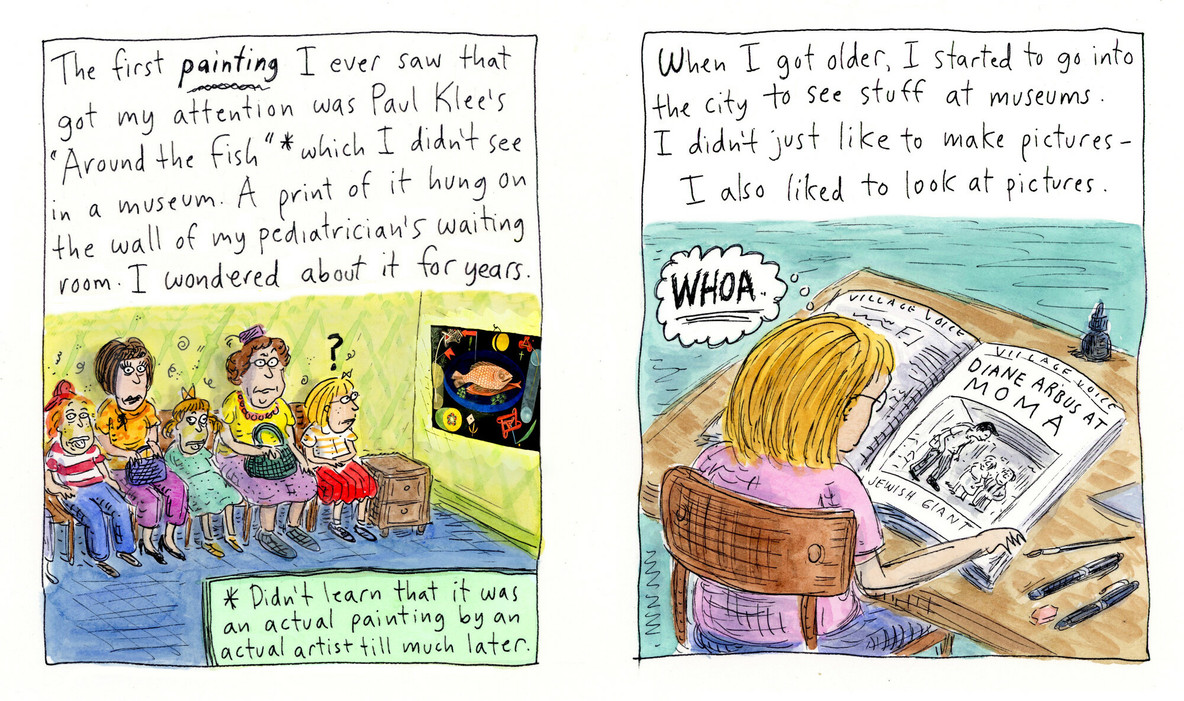

In this panel from Roz Chast's "Museumland," words and images complement each other to produce an immersive effect.

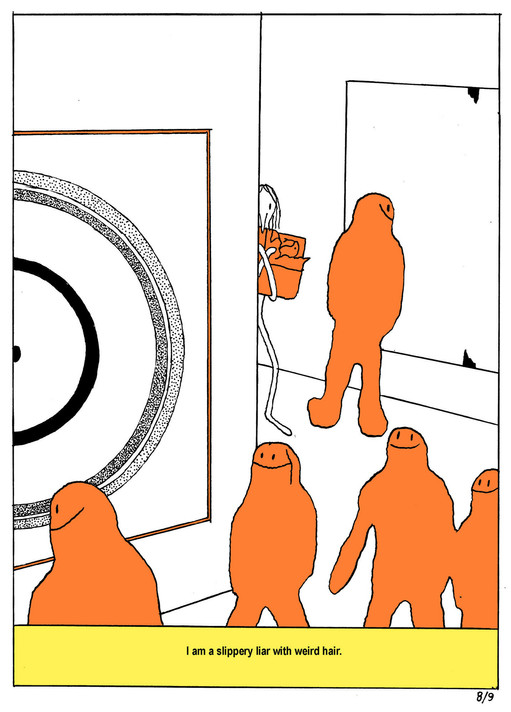

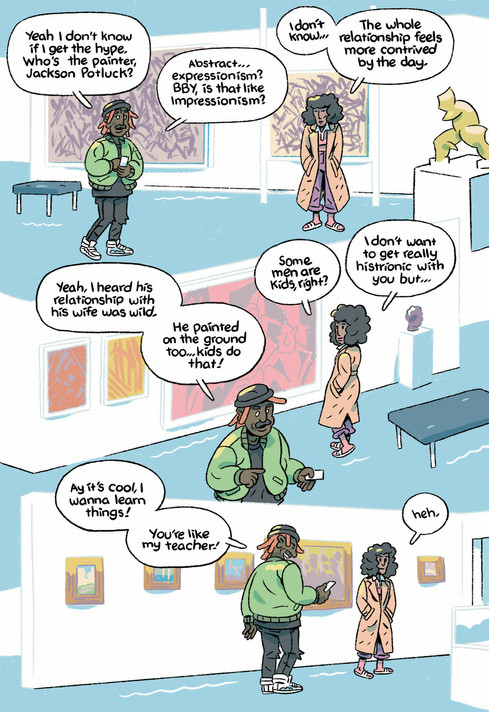

This panel from Ben Passmore's "This Is Tough" shows how words and images diverge in comics. When one of the characters says, "Some men are kids, right?," it's unclear whether she's referencing the Jackson Pollock painting or her partner.

Drawing Inferences

Illustration by Gabrielle Bell for Drawn to MoMA

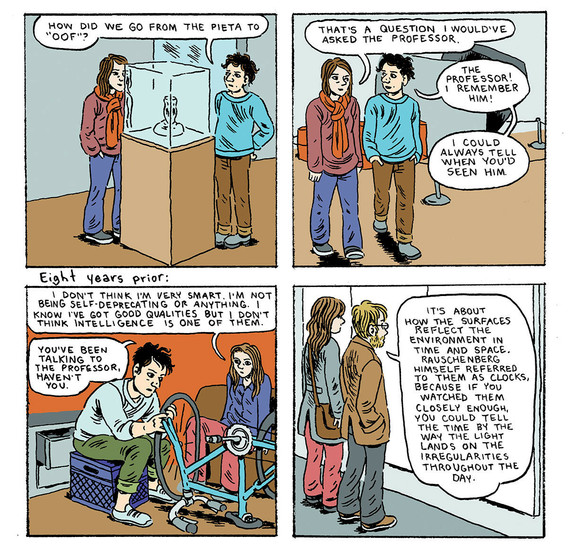

Two consecutive panels by Grace Robinson for Drawn to MoMA

You can still move forward in time, but why not make the leap unexpectedly long? A newborn baby in a woman's arms placed next to a gravestone could suggest a range of story events: The baby was born, lived a long life, and died. Or maybe the baby died shortly after being born. The first interpretation assumes that decades occurred between the two depicted moments, while the second might imply that only a week has passed. Add words, and the possibilities widen. The meaning of the baby and gravestone changes when paired with the caption, "After meeting her niece for the first time, Jo visited their mother's grave."

Putting It All Together

We've talked about the ways images and words look and how they relate to one another. One last thing to consider is their arrangement. Once you have a couple of images, start experimenting with their placement on a physical or digital surface. Some comics only have one image per page, and that's fine, but if you have two or more, you'll need to consider how they go together—which is called layout in traditional comics.

Layout guides a viewer's eye through the images, creating a path. If your comic starts with two images, are they side by side, creating a row? Or are they arranged vertically, creating a column? Add a third image and the options grow more complex—though not necessarily. You might default to a Z-path, the most conventional viewing path, because it imitates the flow of words in English prose, offering the easiest path for the viewer to follow. There's nothing wrong with using conventions—as long as you know they're just optional.

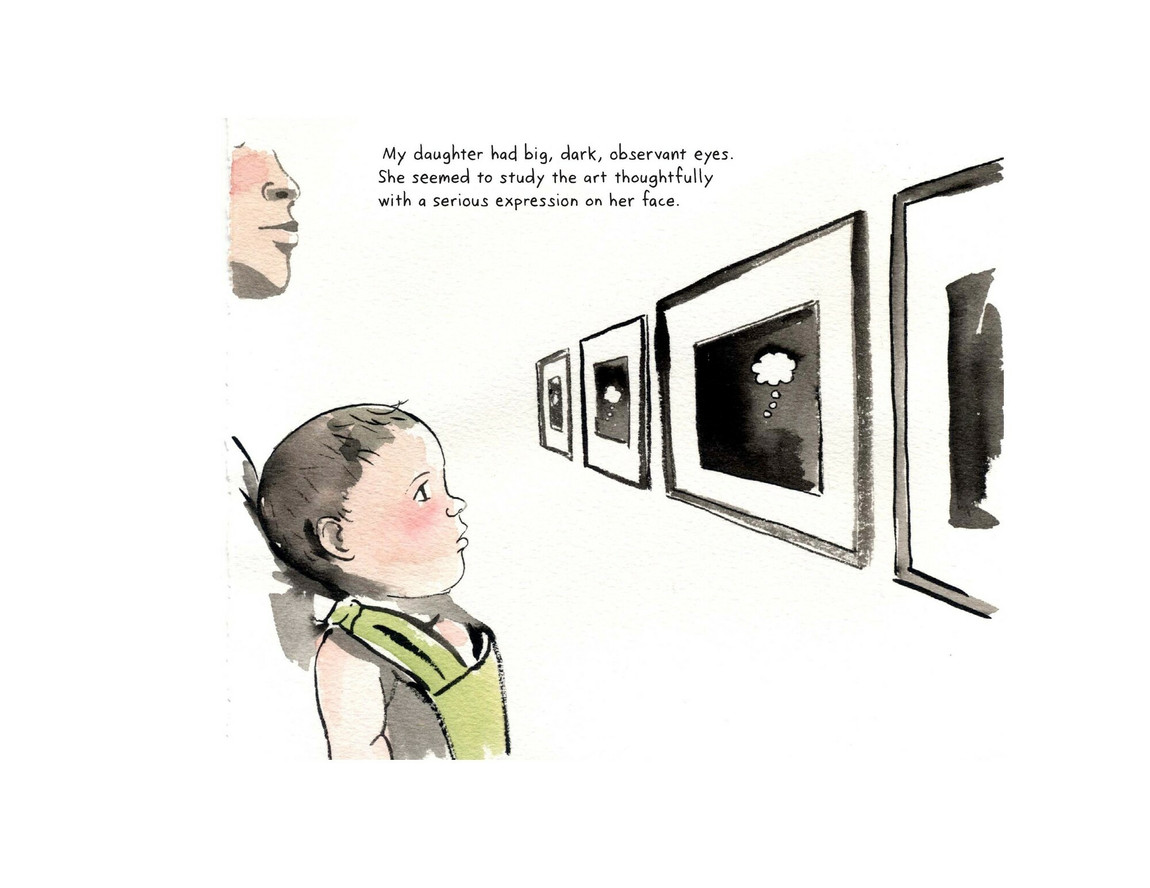

Danica Novgordoff's Drawn to MoMA deviates from conventional reading paths. Instead of organizing pages with a grid of multiple images, each page contains a single image.

Conventions also give you a way of highlighting certain moments by suddenly breaking from expectation. If all of the images on a page except one are the same size, the content of the larger image becomes more important. You can also accent an individual image by giving it a different frame, or no frame, or a differently shaped frame, or a tilted frame, or a different amount of white space around it. You might also group certain images together with the same techniques, drawing further connections between images that share size, shape, framing, or spacing qualities.

Experiment with different arrangements to find something that feels true to the content you're creating. Usually that content is called a story, but like everything else we've discussed, this is just another convention. If you're creating an abstract comic (picture an evolving sequence of Pollock-like drawings), then you might throw that convention out, too. The comics form has remarkably few rules. Don't box yourself in unless you decide to.

Illustration by Joanna Avillez for Drawn to MoMA

Try This!

Now that we've heard from Chris about the elements that make comics unique, we invite you to consider the relationships between words and images with these creative prompts.

Play with Style

Partner up with a friend or a classmate and draw an illustration to accompany the following sentence: "Jo watched sitcoms all night." You can take as long (or as short) as you'd like. Just be sure to keep your illustrations a secret until you're both completely done. Then, compare your drawings. What elements in your drawing represent your style?

Transforming Words

Take some inspiration from Ed Ruscha's OOF and think of a word or sound that you find intriguing. Say it aloud and reflect on how it makes you feel. Type your word using Google Slides or any app or program that can design and customize text. Select a typeface and size that best illustrates your word. For example: if it's a "soft" word, you may want to use a small curvilinear typeface, or a large angular typeface for a "loud" word. Play around and try out different colors for the letters and the background. How do the colors react to each other? How do they make you (and others) feel?

Words in Pictures

Artists like Dorothea Lange understood how including signs, such as billboards and hand-painted notices, could help convey the story of a place, time, and people. Explore your home or neighborhood and take a photograph that includes words. How do the words influence your understanding of the photograph? What stories could you craft around your photo?

Connecting Images

To make his Marginalia series, artist Iñaki Bonillas pulls out photos from the books on his shelves and makes inferences by combining them into one image connected by a single theme. Find two images from different sources—we recommend looking through magazines, advertisements, books, family photographs, or even old drawings you've made—and place these images side by side. Take some time to find similarities between the images, either in subject matter, place, characters, or symbolism. What relationships do you see, and how would you explain your reasoning? If you had to put the images in sequence, which one would come first? If needed, write a caption that will make your inferences clearer.

Cartoon Creates Their Own World With Their Drawings

Source: https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/621

0 Response to "Cartoon Creates Their Own World With Their Drawings"

Post a Comment